History of Cake decoration in the UK

Did you know that the term ‘sugarpaste’ (aka fondant in the USA) arose in Manchester, England, in the 1600s? It disappeared back into literary obscurity soon after. In 1970s Renshaw’s attempted to relaunch sugarpaste however this attempt failed. Tombi Peck and Elaine MacGregor were the sugarcraft lobbyists (early 1980s) - they persuaded Tinkertech to create metal flower cutters and Sugarflair to produce food colours (liquid/pastes and petal dusts). They also persuaded Renshaw’s to amend the sugarpaste recipe, which was then relaunched as ‘Regal Ice’ a name suggested by Elaine’s husband, Steward. And the rest, as they say, is history - within a decade, sugarpaste had become the main covering medium of celebration cakes in the UK.

It was Mrs Elizabeth Raffald of Manchester, who first introduced the combination of bride’s cake (plum cake), almond paste and royal icing, in her 1769 book ‘The Experienced English Housekeeper’. Prior to this, fruitcakes were typically coated solely with marzipan or Royal Icing. Should Royal Icing be applied directly to the plum cake, there was a high risk of cake crumb in the icing, as well as fat leaching out and creating a yellow stain on the icing surface.

Most of the Royal Icing piping techniques we rely on today were created by a handful of confectioners in the late 1800s and early 1900s. I tend to think of this group as the founders of UK piping, despite most of them learning their trade on the continent – the likes of Herr Willy, Ernest Schulbe, Erwin Shur, George Cox and S. P. Borella.

Herr T. Willy

Born 1849 (Germany) and dying at the age of 60 in 1909 (London).

- Commenced his confectionery training in 1863 (aged 14 years)

- Arrived in the UK aged 32

- ‘All About Piping’ published 1891 (125 years ago)

- Previously worked in Germany, Austria, France, Russia, and Switzerland.

Herr Willy, like many cake decorators, was passionate about the craft and strived for perfection… as he saw it. The preface of his 1891 book could be considered almost libellous, to this effect. It is available for free online: https://archive.org/details/b20386680

The icing known simply as ‘white icing’ on the continent was our Royal Icing, having upped its status after Queen Victoria’s wedding cake in 1840. The Royal wedding cake was only a single tier, weighing around 300 lbs (136 kg). The circumference was 9 feet (270 cm), diameter 34 inches (85 cm) and depth 14 inches (35 cm).

Upon arrival to the UK in 1881, Herr Willy was appalled by the low standard of piping and cake design. Simply put, UK confectioners did not have the proper equipment – the piping nozzles available were useless to the point of being a hindrance, while the piping bags were “monstrous”. The bags were constructed from Indian rubber with screw fittings to attach the nozzle, which Herr Willy states “were in fashion over 75 years ago, when our grandfathers were in the trade.” The solution to this problem? Herr Willy created and marketed his own range of brass piping nozzles, of which there were 160 varieties. He also produced special paper, solely for use as piping bags.

In this day and age, most of us have forgotten that eggs were seasonal. Those available in the winter months were often expensive as well as old, so it would not be uncommon to find a portion of the dozen had gone bad. Herr Willy promoted the use of dried albumin, for consistent and cheaper results. To promote his methods, it was possible to attend his own cake decorating school within London, with twelve lessons available for two pound ten shillings (approx. £280 by today’s money). With each of these lessons lasting around 90 minutes, that’s a pretty good deal, even by today’s standards.

Ernest August Schulbe

Born Halle Germany 1862

Married Minnie (Wilhelmina?) who was born in Kiel, Germany 1861

She died 1909 aged 49. They had five children Mase, Albert, Ernest, Dorothy and Edward. Ernest Schulbe became a British subject in November 1900. He died in March 1942 aged 80.

Out of all of the founders of royal icing in the UK to my mind Ernest Schulbe did the most, however a lot of the piping techniques he created are now credited not just to other cake decorators but to other countries. In the USA they refer to ‘Lambeth’ Joseph Lambeth owned/ran a cake decorating school in the USA he taught ‘Traditional English over piping’ his work was nice, but he did not create any cake decorating techniques. South Africa was known for wing work (large piped lace pieces which were secured over the corner edge of a cake), wing work was originally created by Ernest Schuble in the UK. Extension work (piped lines which extend beyond the cake) originated in the UK not Australia.

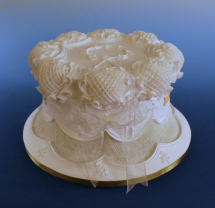

Ernest Schuble first competed at the London exhibition in 1894 where he won the first of many competitions. His style of cake decoration was for every changing, so it was hard for his followers to keep up with his latest style. Some of his designs using net nails (he created and marketed 15 types of net nails) to my mind would still be classed as ‘wacky’ by today’s standards see example. Like Herr Willy he marketed his own range of piping nozzles – however he was of the opinion that a set of 18 nozzles was all that anyone would require. He ran his own Confectionery School of Art in Withington, Manchester. By 1897 his pupils were also wining competitions. He also taught cake decoration at various location within the UK. A private lesson cost £3.15 for 12 hours tuition. He also offered ‘Practical lessons’ where the pupils (max of 2 at any one time) were expected to work in his bakery under his supervision (a for runner to todays ‘internship’?) at a cost of £5.25 for 1 week and £10.50 for 4 weeks

He wrote two books – Cake decoration first published 1898(it was a very popular book and was reprinted several times) he designed this book with the idea that every bake house (bakery) would have a copy on the shelf and the designs held within would be used daily for their customers. This is the first time a top view of the cake design and side view were shown (a forerunner to today’s work drawing) which were to be used as a method to instruct how to create the designs. His second book ‘Advanced Piping and modelling’ was published 1906. Even after 108 years to my mind a lot of his comments are still valid – ‘you cannot learn piping properly unless you have lessons from someone capable of doing good work, and who is able to interpret to others how to do it’.

George Cox

Author of the book ‘The Art of Confectionery’, with illustrations by W.H. Atkins was first published in 1901. By 1903, the book was reissued with an additional 80 pages, introducing even more inspirational techniques and designs. Admittedly the main aim was to promote City and Guilds certified courses, linked to his employer, but this did improve the training and standard of workmanship country-wide.

The City and Guilds body came about in 1878, creating a national system of accredited technical education, allowing recognition of skills for tradesmen. This organisation has been linked to the Royal family since King Edward VII (1881), who was the first City and Guilds president. Queen Victoria introduced a Royal charter for the institution in 1900. Continuing this theme, the Duke of Edinburgh took over the role of president from 1951 to 2011, until he was acceded by the Princess Royal.

To ensure the growth of these certified courses, many local colleges agreed to run and examine to the City and Guilds standard provided a minimum of six confectioners registered their interest. If this minimum could not be met, confectioners could instead study independently via Cox’s book, The Art of Confectionary, then travel to take the exam.

At the turn of the 20th century, stacked cakes were still the celebration cake of choice, but with pillars and separators becoming a focal point of design. This aided the tradition of the ‘first cutting’ of the wedding cake by the bride and groom, by making the lowest tier more accessible. With the icing being relatively thick and hard, confectioners began to ‘pre-cut’ the first slice. After covering the cake with a layer of marzipan and allowing skinning, a wedge of cake would be cut and removed, then returned to the original position. The whole cake and drum (typically 13 mm thick board) would then be iced over with multiple layers of Royal Icing, with the wedge continually removed and re-inserted with each layer. On completion of the final coat (typically coat three, with standard wedding cakes), this wedge would be marked with a satin ribbon, allowing the bride and groom to give the illusion of cutting the cake with ease.

It is a common misconception that dummy cakes are a modern idea, while in fact ‘fake cakes’ were in heavy circulation during the 1900s. These dummies were available in various materials, but cardboard was the most common. Colleges tended towards wooden or metal dummies, as these could be readily cleaned and reused. Some of the most eye-catching pieces in The Art of Confectionary are the designs requiring a cake to be clamped vertically. Lines are piped with gravity, and not against, to ensure neat and even designs – in the pictured case, a double curve. Various vertical cake clamps were available at that time, although most were homemade, with the most basic impaling a cardboard dummy with wire between two plinths. The more modern example shown here is only suitable for dummy cakes, as the weight of a real cake would cause irreparable fractures to the cake structure. Historically, the vertical icing of real cakes had been achieved, albeit only for Royal Icing-coated fruitcakes speared on a larger metal spindle. Sponge cakes do not have a firm enough texture for this kind of clamping.

Edwin Shur

Born in 1866, in the municipality of Obertiefenbach, Germany. As a young man, he moved to London to pursue sugarcraft. He remained in England up until his death in 1930.

His work often inspired awe, with Edwin being a master of both modelling and piping. Our knowledge of his craft largely comes from reviews and competition notes, however, as there are very few photographs of his work in existence. He was resident in London for a fairly short time before he began to enter sugarcraft competitions, and he was a pioneer for piping lace pieces. The technique was displayed for the first time in 1897, on a competition cake for the London Bakers’ and Confectioners’ Exhibition. As is standard with many of the forefathers of sugarcraft, their work has been wrongly attributed over the years – in this case, lace pieces have come to be more associated with S. P. Borella, who used piped lace pieces on his own entry a year later.

Edwin Schur commemorated his work in two books, the seminal ‘Progressive Simplicity in Cake Decorating’ (early 1900s) and ‘The Simple Method in Artistic Cake Decorating’ (1910). He was also a co-author of The Modern Baker, Confectioner and Caterer, A Practical and Scientific Work for the Baking and Allied Trades (1907). As is sometimes the case, greatness begets greatness. In this case, Edwin Schur also introduced his son, Frederick, to the craft. Frederick Schur has his own entry (further down)

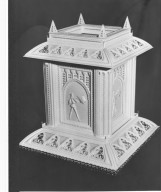

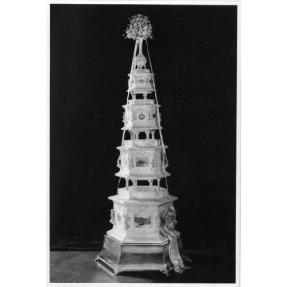

Schur might be best remembered for a comerative cake he created, for the Confectioners’ and Grocers’ Exhibition of 1913. The piece was a three-tier hexagonal cake stack, standing 4.85 m (16 feet) high, with a hexagonal base board (measured flat to flat) of 2.25 m (7 ½ feet). While the original intention was to use real cake, this was not feasible; the estimated final weight would have been in the region of 8128 kg (eight tonnes). Instead, the piece was constructed from a series of wooden dummy cakes. The end result was still heavy, with approximately 250kg (550 lbs) of sugar used to coat the dummies. An additional 340 kg (750 lbs) was added through piped decoration and modelling (a combination of pastillage and chocolate). The pillars between the two tiers of cake were constructed from wood which was then gilded. The pillars were 45 cm and 37.5 cm (18-inches and 15-inches) in height.

As a side-venture to his design work, Edwin Schur also produced and promoted the use of moulds within the ‘bakery trade’. His moulds were very similar to those used today, both as plaques or whole-side designs. The aim was to significantly reducing the decorating time required for general cake sales. The moulding icing referred to as ‘sugar paste’ needed to be made by the baker (there was no ready-made available unlike today) from egg white, gum tragacanth, fat and icing sugar.

Edwin Schur was also a gifted public speaker and demonstrator.

Secundo Pierro Borella

Born 1864 in Italy. As with many of the other confectioners, he moved to the United Kingdom as a young man in the 1880s. He resided in Cheltenham, Gloucester for a short time before moving to London. In 1898 at the London Bakers’ and Confectioners Exhibition he entered a competition piece which showed the new technique of piped lace pieces (this technique requires the royal icing lace pieces to be piped onto a piece of waxed paper, once the piped pieces have dried, the pieces are released from the paper and carefully attached to the cake surface with a small amount of royal icing) over the years this technique has wrongly been attributed to him where in fact the creator of the technique was Edwin Schur.

In 1906 he followed in the footsteps of his predecessor, Ernest Schulbe, and taught at various locations in Scotland before finally moving his family to Scotland, where he became a teacher in confectionary at the Royal Technical College of Glasgow.

During his formative years in confectionary, he collaborated heavily with the author H. G. Harris in the creation of several 'All About...' books, which covered topics ranging from pastries, biscuits and gateauxs to the more niche and advanced Genoese glace and petit fours. These books were released between 1903 and 1920.

S. P. Borella also published his own work, which was heavily inspired by the revolutionary guide format of Schulbe, in that his book 'Cake Tops and Side Designs' features separate images of both the side and top decorated pieces. However, he improved on Schulbe's method by showing the piped design at various stages, allowing the reader to follow more clearly the path to replicating his designs. Many of us are very visual learners, and with pictures being worth around 1000 words, this book was indispensable for confectioners. If you have picked up any of the more recent cake decoration books, you'll see that S. P. Borella's innovative format is still the preferred method of written teaching today.

He dedicated this book to his friend and mentor Sir Alexander Grant. You may recognise the name, as Sir Alexander Grant is best known for inventing a digestive aid commonly referred to as 'the digestive biscuit'. Sir Alexander Grant later went on to become the chairman and managing director of McVitie and Price (now United Biscuits), where S. P. Borella worked until he retired.

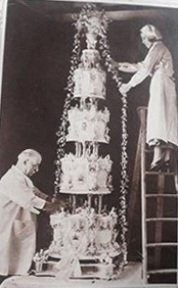

Borella's work was recognised by the higher classes, a privilege which resulted in his producing no less than 33 cakes for the royal household. It is possible to watch a short video clip on British Pathe which shows S. P. Borella (at the age of 70) and two other confectioners setting up the wedding cake of Prince George (Duke of Kent) to Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark, in 1934. The cake itself stood 9 feet tall (270cm), weighing a massive 800 lbs (363 kg).

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/the-royal-wedding-cake/query/cake

George Fredrick Burton

Born1890 Blackpool, Lancashire, UK

Father Ralph Bramwell Burton (confectioner), mother Margaret Alice Burton

Parents owned a bakery in Park Road, Blackpool, Lancashire. All the family worked in the bakery. His Great grandfather George Burton was the author of ‘The Art of Baking’ published 1866

George created the first royal icing piped ‘flange’ on a competition cake (see example) which is run sugar panel placed at a sloped angle around the base of the cake. This style of decoration requires great skill – as the icing consistency needs to be spot on (too thick and the finished piece will be uneven, too thin and the royal icing will run to the base edges of the curve). This style has been copied by many the main ones being Ernest Cardnell (author of the Nirvana books) and Ronnie Rock both of these people have there write up (further down).

George market/sold metal stencils – inscriptions as well as/pictorial as a quick/cost effective way to decorate cakes.

George wrote several books on Cake making and icing designs. His book ‘Icing made easy’ originally published in 1928 promoted the use of stencils as a quick way to decorate cakes for the trade/bakeries.

His School of Confectionery was operating in Blackpool in the 1920’s. The Burtons family pioneered bakery manufacturing and technologies. In 1935 his brother Joseph Burton founded Burton Biscuits which became one of the UK’s largest biscuit maker, as Burton’s Gold Medal Biscuit Company and eventually becoming Burton’s Foods. George became Chief examiner with City & Guilds and by 1937 was Head of Blackpool Technical College’s School of Bakery.

Ernest Albert Cardnell

Born 1897 (Burnham, Essex), died September 1975 (Tunbridge Wells?). Unlike the other cake decorators already covered in this series of articles Ernest’s father was not in the bakery/confectionery trade, he was a wheelwright (makes/repairs wooden wheels)

Prior to the 1st world war Ernest was an apprentice at a bakery in Burnham-on-Crouch Essex. After the war, he worked in Harry Nicholl’s bakery in Bexleyheath Kent.

Married Gladys Julia Gibbs 22nd September 1917 Bexleyheath.

Between the two world wars he won many awards at Bakery/Confectionery Exhibitions. He was very much into attention to detail and accurate construction.

Over the years he wrote numerous articles for bakery magazines.

His first book Commercial Cake Decoration published around about 1927 revised and reprinted with an addition 80 pages in the late 1940s. This book aimed as a guidance and reference towards the City and Guilds examination for Design and Decoration of flour confectionery and promoting the principles of cake design, use of colour and colour schemes as applied to cake covering and finishing, lettering. Most of the cake designs shown in this book are decorated with piped scrolls, shells and line work with accents of run sugar pieces. However, unlike today most of the run sugar pieces were created directly on to the cake and not as an off piece.

Second book Advanced piping and cake design published 1950s.Focus on cake decoration which is quicker than the tradition over piping style, also which is more economical re effort, time and materials. There for concentrates on cakes decorated with run sugar pieces (collars/panels/motifs) – as the finished cake will appear bigger to the customer (at no extra charge to the confectioner). The advantage of this style of work is that the various pieces can be created when business is slack, then boxed (stored in various boxes) till a cake of that design is required - its then a quick/simple task of attaching the various run sugar pieces to the cake. In the U.S.A., any cake decorated with run sugar collars/panels is referred to as ‘Nirvana’. However, like a lot of cake decorating techniques Ernest Cardnell did not create this technique (many cake decorators were using this technique long before him) he only promoted it use as a cost-effective way of decorating cakes.

His third book Decorated Cakes and Confectionery published late 1950s

This book by far is my favourite book by Ernest Cardnell. The designs are aimed at the various season incorporating royal icing, marzipan, buttercream, chocolate and pouring fondant.

A recreation of royal iced Ernest Cardnell competition cake. The actual cake is only 5 inches in diameter, but once the run sugar panels, collars and balustrades (55 pieces in total) are attached the actual cake looks a lot bigger. In the 1950s and earlier all cakes were placed on round or square cake borads (no matter what the shape of the actual cake).It was not uncommon to see the piped desig run off the cake board.

Ronald Rock, aka Ronnie

Born 6th October 1916 in South East London (Mitcham)

A new heir to the W. Rock and Sons bakery. Over time he established himself in the local community, marrying one Florence Eleanor and having a son of his own, Peter. Ronnie was and is classed by many as one of the best Royal Iciers that the UK has produced, where he is often referred to as the cake decorator with the golden hands. His contribution to the craft was sadly cut short with his death at the age of 42 from Leukaemia.

Ronnie was classed as a modest man, he was happy to share his knowledge and guide other cake decorators. He was known for being a quick worker in the family bakery. He was right handed however preferred to pipe with his left hand.

His first competition piece was entered at the age of 19, amassing over 60 first prizes within the subsequent decade. His work was considered flawless, his piped bulbs were amazing -they were free from ridges/take off marks and were perfectly round. To support such precision, Ronnie had designed slings suspended from his workroom ceiling, supporting his arms for long periods of pipework. In terms of style, he often relied on flanges (a technique developed by George Burton) but avoided designs popularised by the likes of Herr Willy, Ernest Schuble or Edwin Shur. His work, in contrast, strived for a more minimalistic design with clean, delicate lines. Unlike todays run sugar collars his run sugar collars were double-sided – a high gloss was produced not only on the topside but also the underside.

To produce the necessary consistency of icing for this vision he ground his own icing sugar. One of his competition pieces, created in 1946, is still in existence at the National Bakery School of Southbank University, London.

Ronnie’s impact on other cake decorators is clear, with many of his contemporaries adopting his style of cake decoration and method for circle piping. His obituary refers to the sensation he created at the Dusseldorf Exhibition of 1951, with attendees in awe of the precision and intricacy of his work. Many German confectioners went on to recognise him as Britain’s Royal Icing expert, as he won every class for decorated wedding cakes at the exhibition. He was a master of lace work.

Outside of confectionary, Ronnie’s interests also relied on his focus and precision. With engineering as a hobby, he built various model ships and aeroplanes, holding the record for indoor flying for several years.

Queen Elizabeth’s Wedding Cakes

The wedding of Queen Victoria to Prince Albert in 1840 set a precedent for all the royal engagements that were to follow, particularly with regards to the wedding cake. Queen Victoria had at least 100 wedding cakes in a specially-designated room, created by various companies throughout the UK. The official wedding cake was produced in-house at Buckingham Palace, by their head confectioner.

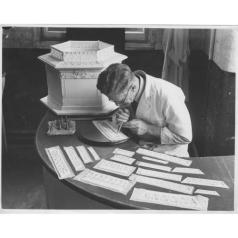

Princess Elizabeth (now Queen) had a paltry twelve wedding cakes for her wedding to Prince Philip in 1947, recognition to the austerity of the war years. Her official wedding cake was produced by McVitie & Price (now United Biscuits), designed and decorated by the company’s Head Confectioner, Fred Schur with the help of a few members of staff.

The cake in question was four tiers, with the total height of 9 feet and weight around 500 pounds. Each tier was double-depth, the cake sizes ranging from eleven inches to twenty-two inches in width. Many of the ingredients used in its production were donated by the Commonwealth, allowing the circumvention of food rationing (which continued to 1954 in the UK) for the historic event.

The design took several weeks to create, necessitating the production of special formers so that intricate curved piped pieces could be produced individually. In all, 700 piped off-pieces were produced and attached to the cake – this number does not include the numerous spare pieces which were no doubt produced in case of emergency.

Fred Schur set to work producing these piped off-pieces, the cakes themselves were left to ‘mature’ over a period of eight weeks. This added more pressure, with the precision of piping essential to replicate the finished design. Were the royal iced coated cakes to be smaller than the design allowed for, piped off-pieces would overlap and look messy; should the cakes be too large post-marzipan and royal icing layers, there would be unsightly gaps.

The piped pieces included plaques which depicted the past-times of her Majesty and Prince Philip, such as horse riding and fishing.

The cake was displayed on a bespoke 30-inch silver stand, manufactured to bear the weight of the heavy upper tiers. The corresponding base boards for each tier varied in depth to provide the correct degree of support/balance, ranging between 1 ¾-inches to ¾-inches.

Frederick Ernest Schur was born on the 2nd January, 1903 in Putney. He was the son of acclaimed confectioner Edwin Schur, one of the UK’s most accomplished decorative artists in sugar and marzipan work. His father has also been referenced in this write up. Fred spent only a brief time working for McVitie & Price at Harlesden before returning to a previous job at Burton Son and Sanders, trade confectionery and sugar importers of Ipswich. Later years saw him train young bakers for Allied Bakeries.

Schur had a prominent role on the Board of the Bakers and Confectioners Association, a group that his father had helped found. The Association aimed to promote the trade skills and idea exchange to enhance businesses, as well as encouraging the study of confectionery as an art form. The group also provided a social intercourse between its members.

Fred Schur is purported to be an excellent demonstrator, excelling and leading others in all aspects of sugarcraft. He died at the age of 78 in 1981, still resident in his native Ipswich.

To commemorate her wedding to Prince Philip in 1947, Queen Elizabeth was gifted an astounding twelve wedding cakes. It is astounding not for its excess, but its austerity – this number pales in comparison to the wedding cakes of Queen Victoria, a sign of the monarchy standing side-by-side with the British public, who were themselves under rationing. None of these cakes went to waste, with the leftovers cut and distributed to various hospitals and armed forces to which she was patron.

Mackie and Sons of Princess Street, Edinburgh, were one of those who were successful in their offer of a wedding cake. They supplied a four-tier pillared wedding cake, 6 ft in height and weighing 120 lbs. It was decorated by the bakery manager, Mr. Patterson, with the help of his deputy, John Thompson and assistants Margaret McLaren and Eddie Spence. Spence, now a renowned royal icer (he will feature in his own article later in this series), had not long started his apprenticeship at the bakery and the job of the royal wedding cake was one of his first tasks. The necessary quantities of royal icing were produced in 10 oz batches, applied as coats and decorations to the cake over several days. The young apprentice had been fully broken in, his hands covered in blisters from the task but his spirit focussed on continuing his apprenticeship with gusto.

The design was inspired by the Scott Monument which stood across from the bakery in the Princess Street Gardens, with numerous hand-piped and flooded royal icing panels. The Coat of Arms of Princess Elizabeth were also included, hand-painted alongside the Royal Standards of Scotland. Each tier was had by four china cupids (5” in height) at the base. The first slice was pre-cut (hence the satin ribbon either side of the panel on the base tier) for ease of the bride and groom.

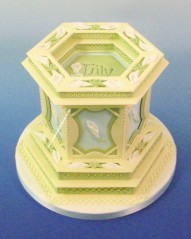

A second cake was supplied by J. Lyons of Cadbury Hall (Bakeries) in the style of Jasper, in blue and white. This cake was also around 6 ft, weighing 140 lbs with a base tier 30” across. It was designed and created by Mr. F. E. Jacob, the company’s chief decorator. The tiers were separated by silver pillars. Twelve Wedgwood Jasper vases (4” height), specially commissioned and created by Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, Barlaston. For full rococo-effect, ‘alcoves’ for these vases were created by removing small semi-circles from the outer diameter of the cake. The front panel was decorated by the Coat of Arms, a naval crown and the monogram E, P for Elizabeth and Philip, and made form satin. The top Jasper vase was larger, a full 7” in height, filled with fresh flowers with trails of orange blossom.

C. H. Elkes & Sons Ltd of Staffordshire began as a small family business, run by Charles Henry Elkes. The Uttoxeter-based bakery was originally a shop in Carter Street (1908) and later High Street, before expanding into the Elkes factory which employed some 1600 people. By 1928 the business was thriving, leading to the creation of Dove Valley Bakeries. Their most popular products included Elkes Malted Milk and London Assorted Biscuits, which could be purchased fresh from two factory-linked cafes – Dove Valley Café and the Elkes Café. The latter was opened in 1932, run by Wilfred Ernest Elkes, son of Charles Henry. The business was acquired by Norther foods in 1985, the manufacturers of Foxes biscuits.

In 1947 Elkes were commissioned by the British Cake and Biscuit Association to produce a Royal wedding cake. The chief decorators at the time, J. H. Hutchinson, P. Houlder and W. H. Smith, produced two identical cakes in fear that one might be damaged in transit. The spare cake was later put on display in Uttoxeter.

This three-tier cake weighed 415 lbs, standing an impressive 6 ½ feet high with its top piece. The base tier stretched 30” in diameter, contributing 240 lbs to the overall weight. Following the typical theme of family crests, the side decoration was heavily influenced by the coats of arms for Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, as well as paying homage to the crests of Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.

The middle tier 20” in diameter, weighing 130 lbs. This tier payed tribute to the Royal Navy, Army and RAF as well as the specific regiments that Princess Elizabeth presided over at the time.

The final, top tier 15” in diameter, at a depth of 9”. It weighed a paltry 45 lbs in comparison, topped by Eros, the Greek God of Love. The design was inspired by the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus.

As a common problem to such large and heavy cakes, there were many worries that the base cake could not hold up the weight of the upper tiers. In contrast to Fredrick Schur royal wedding cake, Elkes opted to stabilised their structure using internal supports – steel rods which would support the pillars between tiers.

All the ingredients to produce this wedding cake were sourced within the British empire – flour from the UK, butter from New Zealand, Sugar from Barbados, eggs from Canada and Northern Ireland, currants from Australia, brandy from South Africa and rum from Jamaica.

A second North West bakery, Bollands of Eastgate (Chester) were also responsible for a Royal wedding cake. This was not their first royal wedding cake, as they made one of the 100 wedding cakes presented to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert upon their marriage in1840.

The cake produced for Princess Elizabeth was vastly different in style to the others. It remained the traditional three tiers supported by hand carved pillars - heraldry-style lions. Four lions supported each tier, each being gilded for extra impact. This cake was also significantly smaller, weighing less than 60 lbs. The side design on the two base tiers feature piped thistles and roses, a tribute to both England and Scotland. The Royal coat of arms and other naval emblems were also used, with the naval theme continued in the top piece – an anchor united with a crown.

Huntley & Palmer started as a small bakery in 1822 in London Street, Reading. By1846 the company had out grown these premises and moved to larger premises o the bank of the river Kennet, by 1898 the company employed a staggering 5,000 people and was classed as the largest biscuit factory in the world. The town of Reading became known as “Biscuit Town”. Over the years, the business diversified and produced other baked goods.

Frederick William Bryant commenced work at Huntley and Palmer at the age of 14 (1869) and continued to work for the company for another 62 years, retiring at the age of 76 (1931) during his working life he created various royal celebration cakes (he died in 1947). His son Jack Bryant (born 1877 Christened Frederick William Bryant) commenced work at Huntley and Palmer in 1913 at the age of 36. He quickly progressed through the ranks, taking over from his father as the head of the Cake Icing Department in 1931. Jacks father came out of retirement at age 79 to help Jack, create the wedding cake for the Duke and Duchess of Kent in 1934.

Huntley and Palmers wedding cake for Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip was originally designed to weigh 400 lbs, but the Palace requested this be reduced for a more austere 195 lbs. This cake was largest of all the cakes in the wedding cake room (the official wedding cake was in a separate room). The wedding cake took a full three weeks (including weekends) of dedicated effort - at a guess, this cake took at least 210 hours to create.

The Four Tier Hexagonal wedding cake was decorated with ornate piping, and no less than 144 off pieces made up of collars, side panels. flanges and balustrades. The top tier displayed the crests of the commonwealth countries. The other tiers showed images of the Royal family and places with royal association. At each corner of the cake stood a china cupid (various poises). A large bow on the base cake signifies that this cake also had a pre-cut section.

A short video clip of this royal wedding cake can be found http://www.britishpathe.com/video/royal-wedding-cake

Jack Bryant was an amazing royal icier you can watch a short video of him demonstrating his art/skill http://www.britishpathe.com/video/icing-artist-beware-other-colour-pics-share-this/query/bryant

The video was created for BBC television programme in 1954 called 'Sculpture in Sugar'. At that time, he had worked for Huntley & Palmers for 41 years.

The Country Women’s Association of Australia sent a 6-tiered pillared, 130 lbs wedding cake. The cakes were baked in Sydney; however, the ingredients were supplied by the Country Women Ass members from every part of Australia. The icing/decoration was done by Mr C. de Mars at East Sydney Technical College. Four small plaques bearing the Australian coat of arms were placed at the base of each cake. Each of the tiers bore the inscription of an Australian State. On completion of the decoration each tier was individually wrapped and placed in sealed airtight tins and then transported by air in several crates. However, during the layover at Lydda Airport (now Ben-Gurion) in Palestine, the cake was damaged. Pastry chef Shaul Petrushka, who worked at Tuv Ta’am on King George Street in Jerusalem was given the job to repair the damaged cake.

My dear friend Eddie Spence has been a prominent figure in cake decorating since the 1950s and has since taught thousands of students worldwide. He started his cake decorating journey in 1946 at the age of 14, starting as an apprentice at J &W Mackie’s and Sons (Princess St.) Edinburgh. J & W Mackie’s held a royal warrant, supplying the Balmoral residence with baked goods. One of his first jobs was to produce the royal icing used for Queen Elizabeth’s wedding cake – an arduous task, mixed by hand in 10 oz batches.

Eight years later, Eddie was the head of J & W Mackie’s cake decorating department. He made several changes at the bakery, including increasing the depth of their fruitcakes. This avoided the practice of stacking two cakes to achieve the necessary height and reduced the amount of marzipan required, reducing cost.

He also had wider-ranging effects on the general cake decorating community. The practice of piping off-pieces onto sheets of acetate was initiated by Eddie, who was inspired by the work of J & W Mackie’s chocolate department. He also designed his own competition-grade piping nozzles and had then produced by a local jeweller – the tips were drilled to be perfectly round, instead of the more conventional flat sheet metal which is rolled and soldered to a tip. It was these nozzles he used on royal celebration cakes, to create a flawless design.

The bakery competed in numerous competitions during his time, winning in the UK and abroad. For every competition or royal piece, the cake and decoration would be produced in triplicate, so that only the best would be submitted.

Eager to encourage and teach younger decorations, Eddie began to teach evening classes at the Edinburgh baking school after a full day’s work at the bakery.

In 1969, J & W Mackie’s and Sons was bought-out by United Biscuits (McVities). Eddie took this as an opportunity to move to Derby with his wife, Betty and children Debra, Derrick and Paul. He continued to submit pieces to competition, and following the East Midlands Exhibition was approached to teach at Kedlestone Road College, Leicester.

In 1978, Eddie and his wife moved to Bournemouth to work for Mary Fords. Eddie was appointed head tutor while his wife was in charge of the dispatch/mail order side of the business. In subsequent years, he created several royal wedding cakes, including those of Prince Charles to Diana Spence and Prince Andrew to Sarah Ferguson. Mary Fords produced their first book 101 Cake Designs in 1982 a large proportion of the work contained in this book was created by Eddie.

In 1986, Eddie moved into full-time teaching, acting as a tutor in cake artistry, bread making, flour confectionary, colour design and calligraphy at Sparsholt College, Hampshire. He was also a regular tutor at Squires kitchen and featured on TV several times.

In 1997, Eddie produced the cake for Queen Elizabeth’s Golden Wedding anniversary. Due to the weight (approx. 10 stone), it required four people to carry it on a specialised base. Sadly, Eddie’s beloved wife Betty died in 1999. Eddie received an MBE for services to the industry in 2000. He finally published his own book, The Art of Royal Icing in 2010, which has been reprinted several times.

Eddie re married in 2017 – Tracy has been his right-hand person for a number of years.

Late 1950s to 1970s

With the ever-changing trends in cake design, skills are continually lost only to be relearnt when that style comes back into fashion. One example is found in a popular book of the 1950s – Cake Design and Decoration by L. J. Hanneman and G. I. Marshall – which has been reprinted several times (most recently 1979, 4th edition). It covers the geometric principles of cake designs, such as with collars and flanges, a topic which quickly fell out of fashion and was not seen again until the 1980s in The Art of Royal Icing by Audrey Holding and Confectionary Design by Lindsay J. Bradshaw. That is not to say that all cake design fashions are cyclical – the Hanneman/Marshall book also featured chapters on Heraldry, a now relatively obscure technique which was commercially commonplace at the time. Many bakeries following World War II struggled to meet fresh demand and opted for rapid decoration techniques using mass-produced silk/plastic flowers with paper leaves. The previous and more time-consuming technique of producing decorations from pastillage or gum paste became almost unheard of with the ease of non-edible decoration pieces. It wasn’t until the 1960s saw a resurgence in recreational cake decoration that we returned to producing our own decorations.

During the resurgence in interest, many local schools began to host vocational (non-certificate) evening classes in decoration. If you were married in this decade, then it was typical to have the wedding cake produced by a relative or family friend. The home decorator had very little equipment available to them, as moulds and cutters tended to only be available to the bakery trade, resulting in freehand sugar flowers and models.

In 1967, Evelyn Wallace published her first book – Cake Decorating and Sugarcraft – which has also seen a succession of reprints up until 1986. This was one of the most influential books aimed at a home-based decorator, with all previous publications in confectionary being aimed at commercial production. Evelyn herself trained in Manchester and became a teacher of domestic science at several schools and colleges in the UK. In the latter portion of her career, she became joint editor of a cookery and cake decorating magazine as well as a writer. Evelyn is credited with creating the term sugarcraft and popularised the term through her extended travels as a cake decorating tutor in Canada, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Texas, Washington and New York. A little closer to home, Evelyn was the first Honouree President of the British Sugarcraft Guild (1978).